In the wake of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s landslide victory in the recent parliamentary elections, observers are now discussing the prospects of a new phase in the role their country is playing in the world.

Indian experts believe that "the world is moving in the direction of multi-polarity, albeit asymmetric, which in the long haul can turn into a US-Chinese bipolar system." According to them, New Delhi is wary of China’s claims for global dominion. Simultaneously, the current Indian government has set itself ambitious, long-term goals aimed at strengthening the country's international standing as a “serious global player,” while creating new opportunities for speeding up its development and economic growth. The experts also believe that India can gain a full-fledged status of a great power only if it manages to "independently create multilateral organizations that would safeguard its interests and express its values" [i]. One of the most realistic scenarios being contemplated is developing a strategy of “counterbalancing” China to combine “new and revived functional initiatives of regional economic cooperation, as well as models of sub-regional integration” [ii].

India is now trying to counterbalance its growing strategic partnership with the United States by strengthening and diversifying ties with Russia and building a comprehensive interaction with China.

The developments currently unfolding in Greater Asia and the Asia-Pacific region, which the Americans and many others now call the Indo-Pacific Region (IPR), apparently favor India. Almost all countries having interests in this vast area, which is gradually turning into one of the world’s primary regions, now want to work closely with New Delhi in an effort to achieve both their tactical and long-term strategic goals. This means that without India’s participation, let alone with the open opposition by its leadership, neither Washington’s IPR project, nor Beijing’s “Community of Common Destiny” concept can be fully implemented. Without India the Chinese project remains incomplete, downgraded to a trans-regional status from a continental one. The same with the US’ Indo-Pacific strategy which, in the event of India’s departure, will essentially lose one of its two main pillars. [iii]

However, experts believe that, objectively speaking, both these initiatives assign New Delhi a supporting role, while India is yet to formulate its own big concept, its strategic vision of the future of Asia. India also wants to retain for itself maximum freedom of maneuver and flexibility in international relations and uphold its claim to be the "system-forming" power of South Asia. Meanwhile, the interest of Washington and Beijing, which are struggling for dominance in Asia, in adding a third equal “pole” to what is happening, is apparently situational and limited just to certain aspects of their relations with India. Europe, for its part, may be prepared to recognize and support India’s growing sway, but is equally burdened by its own problems.

The geopolitical aspect of relations between India, China and the United States is thus becoming increasingly complex and multifaceted. On the one hand, Beijing and New Delhi both recognize the objective need for mending fences, with China interested in ramping up cooperation with India, all the more so amid its current standoff with Washington. On the other hand, systemic factors holding back a qualitative improvement of Sino-Indian relations remain too significant. First of all, these are the struggle for spheres of influence in Asia and India’s growing economic lag from China. Hence the steps being taken by New Delhi to contain the spread of Chinese influence across the vast region stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. New Delhi is openly probing the possibility of cobbling together coalitions, which would have a certain anti-Chinese tilt, primarily by building up ties with the United States, Japan and, probably, also with Australia as part of the hypothetical "Asian Entente." India is also counting on Shiite Iran in its effort to offset Beijing's growing influence in Sunni Pakistan [iv], which is India's “main historical adversary.”

As for the US, it also needs India, primarily as a counterbalance to China. Washington calls India a “vital partner” in safeguarding its interests across the entire Indian Pacific region. Washington is also making clear to New Delhi its desire to ramp up its current confrontation with China beyond purely economic issues. Simultaneously, Washington’s political goals for the long haul are multidimensional: to check China’s growing sway across Greater Asia, including in Pakistan; to prevent a military-political alliance between China, Pakistan and Iran; maintain leverage over India by acting primarily via Pakistan and Afghanistan. Donald Trump’s current policy vis-à-vis Pakistan is objectively prodding that country to take more decisive action in Afghanistan. This is also playing into the hands of those in Pakistan who are the most unswerving supporters of confrontation with India. Meanwhile, any escalation of tensions between New Delhi and Islamabad could bring about a new cool in relations now existing between India and China. US political observers are certain about the incompatibility of the fundamental interests of these two countries, which they believe are “doomed” to remain strategic rivals in the entire Indian Ocean region. Chances are high, therefore, that the two Asian giants will remain stuck in a “midway” position for years to come. “Between not being ready to give in and not being able to move forward,” as some experts put it.

A relatively sluggish pace of socio-economic development remains the main obstacle to strengthening India’s position in Asia and elsewhere in the world. India suffers from the “standard growth diseases” that normally come with accelerated changes in the economy and social sphere. Social inequality is increasing, corruption is widespread, the country is short of natural resources, and the environmental situation is deteriorating. Add to this recurrent terrorist attacks, manifestations of separatism and vestiges of traditionalism constraining efforts to modernize Indian society. Hence the intense discussions, which are being held “regarding the sustainability of current models of socio-economic development.” [v]

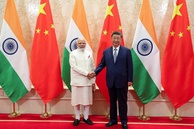

In its effort to rectify the growing imbalances in the country’s development, the Modi government is preparing and is already implementing large-scale reform programs in the economy, administrative and financial spheres. The authorities say they are going to bring the national GDP to $5 trillion by 2024. With the country’s need for investments increasing, the primary goal now is to lure investors from both China and the United States. Chinese money is not only breathing new vigor into India’s economic development, but is also becoming a factor in smoothing out existing contradictions. Following a brief worsening of relations in the summer of 2017, the leaders of India and China still managed to achieve a positive "balance." Whether this equilibrium remains a balance of forces or becomes a mutually-beneficial long-term cooperation remains unclear though.

India’s leaders pinned high hopes on the United States, but with the change of guard in the White House in early 2017, Washington embarked on a policy of bringing US investments and industrial capacities “back home.” Coupled with fundamental trends in global capital markets, this has led to a significant drop in US investors’ interest in sinking their money into projects in India. Moreover, in June 2019, President Trump declared what was essentially a trade war on India, depriving New Delhi of trade privileges that allowed duty-free deliveries of up to $5.6 billion worth of Indian goods to the US market. [vi]

Adding a new twist to the tension, India decided to buy batteries of S-400 air defense missiles from Russia, and Washington demanded that New Delhi roll up its mutually-beneficial cooperation with Iran. Finally, India is seriously worried by Washington’s plans for the future of Afghanistan following the formal withdrawal of US troops from that country.

All that being said, however, Mukesh Ambani, the chairman and managing director of Reliance Industries Limited, India’s largest holding company and, according to Forbes magazine, the richest man in India and all of Asia recently made light of the emerging slowdown of the national economy calling it a “temporary phenomenon.” [vii]

All this gives Russia a good chance to play a stabilizing and creative role here. On December 1, 2018, the leaders of Russia, India and China met for the first time since 2006 on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Argentina. During the meeting, proposed by Russia, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi called for "closer coordination of the three countries’ approaches, primarily in the field of security and building constructive interstate relations in Eurasia." They also underscored the partnership nature of relations between Beijing, Moscow and New Delhi, and the coincidence of their interests and goals “in the field of development.” [viii]

“Moscow has been very helpful to its Indian partners in resolving a wide range of issues - from high technology and defense all the way to building modern infrastructure and reducing poverty,” the Russian Council on Foreign Affairs said. New Delhi is showing a great deal of interest in collaborating with Russia within the framework of the BRICS and the SCO. Meeting ahead of Prime Minister Modi’s visit to the 5th Eastern Economic Forum to be held in Vladivostok in September, Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Yury Trutnev and Indian Minister of Trade and Industry Piyush Goyal discussed measures to increase bilateral trade turnover to $30 billion by the year 2025. The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is one of the most promising long-term joint strategic projects for India and Russia.

During their second meeting held on the fringes of the June 2019 G20 summit in Japan, the leaders of Russia, China and India praised the highly efficient work being done in a single format to create ”an equal and indivisible security architecture in Eurasia.” [ix] However, India’s balking regarding its joining the projects being implemented as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) demonstrates the lingering contradictions of Indian foreign policy. On the one hand, India has reason to consider itself as a state that, “at the end of the day ... will determine in which direction the geo-economic pendulum will move” [x] in almost the entire Eastern Hemisphere. On the other hand, it remains unclear to what extent India will be able to harmonize its interests between the projects of Greater Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific Region, considering their fundamental geopolitical contradictions.

A multi-vector foreign policy has been a hallmark of India ever since the country gained independence in 1947. To this very day, New Delhi has been trying to stick to this line. Whether to stand for a multipolar world together with Moscow and Beijing ... or to join the US, Japan and Australia and form a ‘quadripartite alliance’ to contain China” [xi] - this is the way the situation is seen by some segments of India’s political establishment. The growing uncertainty of the existing international system is one of the objective trends of the past few decades, and India is just one of many countries simultaneously participating in several rival coalitions, whose real goals often contradict each other.

The views of the author do not necessarily reflect the position of the Editorial Board.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[iv] https://interaffairs.ru/news/show/21468

[vi] According to Reuters, the trade turnover between India and the US in 2018 stood at $142.1 billion.

[vii] https://regnum.ru/news/economy/2688651.html

[viii] http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/59278

[ix] http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/60846

[x] https://inosmi.ru/politic/20190702/245402287.html

[xi] https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3859730

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:02 23.08.2019 •

12:02 23.08.2019 •