“Mari El”, photo (2015)

“Mari El”, photo (2015)

Ikuru Kuwajima is a photographer, artist, writer and translator from Japan. In the past eleven years, he has been living and working in Eastern Europe and various post-Soviet countries including Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan. Currently based in Moscow, he continues with his personal art and documentary projects and is actively involved in the contemporary Russian art scene. Despite being quite young, he has received several prestigious international photography prizes and his work has been published in such prominent media resources as Newsweek Japan, National Geographic, Forbes, Daily Telegraph, Le Monde among others. “I, Oblomov” (2017), a series of self-portraits in typically Russian settings, is one of the most renowned projects he conceived living in Russia. Many of the projects investigate such themes as migration, historical legacy and memory, national and cultural identity. Over the last few years, he has had several solo shows and participated in group exhibitions including the 2d Garage Triennial of Contemporary Art which opens in Moscow in mid-September. Even this year, unfavourable for travelling, Ikuru managed to hold a masterclass in Udmurtia before the pandemic and is now working on the exposition based on the materials of this art residence. Elena Rubinova discussed with the artist his Japanese roots and attitude towards Russia, his ideas of cultural identity, local and global aspects in contemporary art, and, of course, why one of his most successful photo projects is dedicated to the main character of Goncharov's novel.

Ikuru Kuwajima

Ikuru Kuwajima

I guess, any of our readers would like to know why your career as an artist and photographer evolved in Russia. After all, you studied photojournalism in America and could choose any place for your future life and work?

To be honest, I did not make a decision to move to Russia overnight. I would rather say that it worked out gradually and, of course, was a combination of various factors. I first moved to Eastern Europe in 2007, after my university years in Missouri where I studied journalism. Back then I was not sure that I wanted to go back to Japan, but would rather try out another path.

In the beginning, America was interesting and offered some freedom that I couldn’t have in Japan - which is famous for its strict and over-regulated society. After the university one of my fellow students invited me to his native Romania - at that time I already worked as a photojournalist and translator from Japanese to English. After a year in Romania, my choice was to be closer to Russian-speaking countries. So, I lived and worked in Ukraine, then in Central Asia - Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan - and only then in Kazan. I was lucky to be able to improve my language skills in all these countries. I started as a photojournalist, did some commercial photography, but at some point, I realized that it was not my way. Photojournalism is very demanding in terms of following the demand for simplified “newsworthiness”, which tends to consolidate resources for only certain issues while overlooking others. I gradually switched to documentary photography and pursued my personal art projects.

As far as I understand you have, at least, four professional roles - a photographer, artist, journalist and translator. What role do you value more? How do you manage to combine them?

Not sure I can come up with a definite answer, it changes so often. I'm trying to do what interests me most at this stage, so, I guess, it will be fair to say that everything exists in parallel - sometimes it's normal to be an artist, sometimes a photographer, and all the time I live in a multilingual environment. My first language is Japanese, but nowadays, I also translate from Russian into Japanese. However, most of my texts about Japan I write in English.

“Eurasia”, photo series (2012)

Would you agree that the very notion of cultural identity has transformed in the modern world?

It goes without saying that technologies played a crucial role in this process. I myself have been living with this for a long time, and who knows, if it were not for the technology and the possibility of remote work, then most likely I would not be able to implement my projects, living in different countries and cultures. Or I would have left long ago. But apart from technology, the cultural and mental code of the country where you work and live has to appeal to you in a certain sense. Especially if you live in a place for long time. The idea of a mental code is best expressed by the English word “mindset”. Strange as it may seem, Russian mindset somehow appeals to me in many aspects, somehow more than American or even Japanese. Japan is known for a very rigid collective mentality, it is difficult to find your individual voice there, and the society in America is too individualistic for me. In this sense, Russia, like many East European countries, is somewhere in the middle. And it turned out to be decisive.

Has your perception of Russia changed over the years? It often happens that from a distance, certain things are perceived in one way, but when you look up closer…

In my case it was the other way round - my experience in Russia is a lot better than my expectations. Before coming here, my ideas of this country were fuelled by different information from the media which is heavily influenced by stereotypes, including negative ones. Ten years ago, when I was still living in Ukraine and Central Asia, Russia had a peak of racist-instigated crimes, predominantly on a street level. People from different post-Soviet countries who went to Russia to earn money often warned me as an Asian that it was dangerous. At first, I was a little cautious, but then decided to try. By the time I came to Russia, I was much better adapted. In Central Asia, too, there were some difficulties, but in Russia, on the contrary, things were better.

“Tundra Kids” (2015)

“Tundra Kids” (2015)

Japan is known for its genuine love of Russian literature. What do you personally cherish most in Russian culture?

In fact, I can't say that I was well informed about Russia and its culture in advance, let alone prepared for my arrival. In my youth, I was even more into German literature. Of course, like many people across the globe, I was familiar with Dostoevsky's and Tolstoy's oeuvres, but only later I discovered Goncharov, Platonov, Pelevin and some other modern authors. Now I read a lot in Russian. For me the discovery of Russia went in parallel - through literature and live communication.

"I, Oblomov" (2017)

One of your most famous projects "I, Oblomov" (2017) is based on a piece of literature known to every schoolboy in Russia. When did you first read the novel? What’s so appealing about the main character?

I must admit that I read the novel not so long ago – in 2014 or around that time, and did it in Russian. My colleague, a photographer Feodor Telkov recommended me to read it in order to understand the phenomenon of the “Russian soul”. Sure, the translation into Japanese has existed for a long time. A famous Japanese author Shimei Futabatei, who is considered the founder of modern Japanese literature, translated part of the novel in the late 19th century. By the way, a fabulous story is connected with this novel. Oblomov became the prototype of the very first modernist narrative in Japanese literature. Before that time, a flow of consciousness, or and even an inner monologue did not exist in our literature as a technique. It took me over two years to finish the project. The shooting took place in different places, mostly where I had already been or lived - Kazan, Mari El, Samara, Moscow. For me, the figure of Oblomov is a metaphor of Russia, the country that swings between the East and the West. And still exists in that mode.

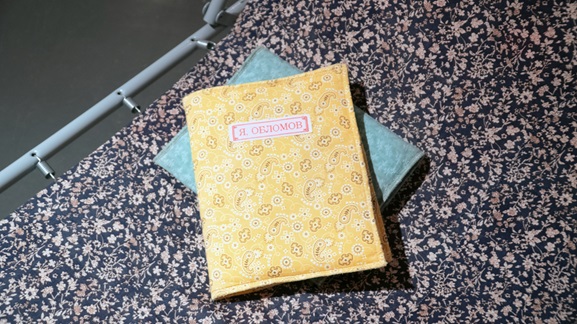

Photobook "I, Oblomov" (2017)

Photobook "I, Oblomov" (2017)

How was the project received in Japan?

In Japan, by the way, the project was well-received. In our fairy tales and legends, we have epic heroes whose archetype reminds of Oblomov. But in America, the project did not "go". My guess apparently, it is not close to the Anglo-Saxon mentality and culture.

Many of your projects you've shot in the remote areas and sometimes stayed with the local families, for instance in the Yamal-Nenets Region, in the Mari El Republic. What has it added to your understanding of Russia and its culture?

If we look at these peoples from the point of view of ethnography, it’s fair enough to say that they are understudied and underrepresented, so, of course, as a photographer I was interested in doing it. At the same time, I try to remove a colonial discourse from my work and look at the modern life of these peoples. In other words, not to experience reindeer riding, but to see how their culture is changing. And maybe because I am also from Asia, the past of these peoples in a sense is even closer to me than America or Europe. Nature, the atmosphere in the villages, and even the climate of Mari El and Udmurtia reminds me of some provinces of Japan. This year I managed to take part in the art-residency, which was held in the Udmurt village of Sep. I very much appreciate this initiative, which is commonly called “socially engaged art”. In this format, communication is art. The process itself, the participation of local residents and communication with them are important. I conducted master classes there and additionally did my own research project, which is related to the generic signs of the Udmurts. I hope that I will finish it by the end of this year.

“Repartiatsia“. Installation, video, photo (2019)

“Repartiatsia“. Installation, video, photo (2019)

The issue of cultural memory is pivotal for your other project "Repatriation", isn’t it? How has it all come about?

The exhibition was held in the spring of 2019 in the Peresvetov Pereulok gallery, and last year this multimedia installation was shown in Krasnoyarsk. It all started off with one fact that I was very interested in. I heard that the shores of Iceland often get trees that drift from Russia. Then I found a scientific article based on studies of the origin of wood thrown out by the ocean in Iceland, originally brought from the banks of the Yenisei River. In the middle of the 20th century, the amount of this wood has greatly increased. According to some researchers, this spike was associated with an increase in logging production in Siberia in the middle of the 20th century - and this coincides with the mass involvement of prisoners who toiled in the timber industry and labour camps. The project consisted of different elements - photos, videos, texts, snags that I collected in Iceland – in this way I’ve recreated this long drift. The portraits of the GULAG prisoners were printed on tree saws. So this project is about nature and people.

“Repartiatsia“(2019) The portraits printed on tree saws.

“Repartiatsia“(2019) The portraits printed on tree saws.

What exhibitions are on your list in the near future?

In September I will participate in the 2nd Garage Triennial of Contemporary Art with my photo project “Trail”. I did this series back in 2013, when I lived in Central Asia. The project is black-and-white photos of a path going for hundred kilometres on the Afghan side of the Pamir mountains. If you are travelling on the Tadjik side you can see this endless route that generations of Afghans used travelling on foot, donkeys, from village to village, from century to century. In our days the path looks as if time is frozen. Especially in winter when I shot it.

A fragment from “Trail” photo series (2013)

What is the role of cultural diplomacy in our days?

In our time of the Internet, despite the availability of communication in social networks, there are various conflicts and problems - many people cannot cope with such a flow. That is why the role of live communication between people only increases.

Photo: courtesy of Ikuru Kuwajima

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:49 08.09.2020 •

11:49 08.09.2020 •