The official presentation of the Nadja Brykina Foundation was held in mid-January in the gallery space in central Moscow where since 2010 Nadja Brykina Gallery has hosted numerous retrospectives and solo shows of the Nonconformist artists of the 1960s-80s as well as artists of the younger generation. The Foundation marked its opening with an exhibition which presents works by Vladimir Andreenkov, Francisco Infante, Alexei Kamensky, Andrey Krasulin, Boris Otarov, Sergey Potapov, and Yuri Zlotnikov to name a few – all of them are gallery artists with whom it has been working for over 20 years. The Nadja Brykina Gallery, which was founded in 2006, is a renowned Swiss gallery focusing on Russian art from the second half of the 20th century up to the present time. In 2010, in order to emphasize its connection to the East European art world and the Russian artists, the gallery opened its branch in Moscow. Besides her permanent activity as a gallerist, Nadja Brykina has been regularly releasing monographs, artists’ books and exhibition catalogues in four languages as well as documentaries exploring the work of selected artists. The newly established foundation aims to arrange exhibitions in museums, promote cultural exchanges and further develop non-commercial projects popularizing Russian art internationally. Our observer Elena Rubinova met Nadja Brykina to ask her how she manages to combine her roles as an art collector, publisher and gallerist, what the foundation plans for the near future and why artists from her collection are characterized as “possessing a painterly vision of the world and touched by the creative power of spirit”.

Nadja Brykina greeted the guests at the opening

By 2006, when you founded the gallery, the Soviet nonconformist art was firmly established on the international art stage and Switzerland was no exception. How did you manage to find your own niche in the gallery business?

I'm afraid it would be an exaggeration to say that at the early stages of our activity when we had founded the gallery in Zurich, a broad audience was that much aware of the Russian art of the 1960s-70s. Even those who were genuinely interested did not know Soviet art in detail and Nonconformists in particular. So, for most of them it was a revelation to discover this kind of art. On the one hand, a serious gallery like Renee Ziegler, which was not so big in size, but followed the traditions firmly, had already put up some Russian shows – back in the 1970s such artists as Ilya Kabakov, Vladimir Andreenkov and some others already had their exposure in the West; two other Zurich galleries ran Anatoly Brusilovsky's exhibitions at some point. But it was a while ago – time changed, and a new generation of collectors and new audiences emerged.

So, I have been deeply engrossed in collecting Soviet nonconformist art since the 1990s, and I clearly realized that it was necessary to set up an art institution of some kind. At some stage I even considered opening a museum, but having closely studied a number of Western art museums, I understood that a museum was usually a great place to visit, but even if its collection had the best 40 Picassos, viewers were in no hurry to come back and look at them again. Back in 2006, we decided to open a big gallery in the centre of Zurich, so that we could work in a flexible format – to put together group shows, including retrospectives that would demonstrate various gallery artists in development – from the 1950s-60s to the present day. The gallery has been in operation for 12 years and we went through many stages: we saw a lot of interest, had good sales and high prices. But it all came with time and effort.

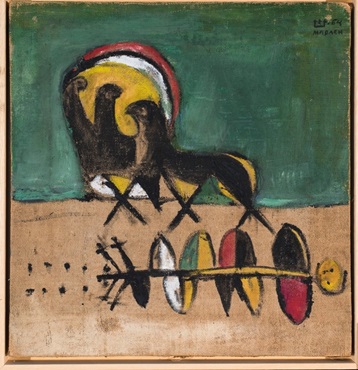

Marlen Spindler. Composition, 1964

What repertoire of Soviet art did the Western audience discover when your collection became known to the audience? As far as I can recollect, Professor Jean-Claude Marcadé, who wrote an introduction to the Russian Museum catalogue, emphasized that artists from your collection “possessed a painterly vision of the world and were touched by a creative power of spirit”.How has it become possible to build such collection?

If we try to describe the situation in the West, it's obvious that the focus has always been on the artists who emigrated from the USSR – they have always been the priority for museums, if not for galleries: they showed works by Ilya Kabakov, Vladimir Yankilevsky, Eric Bulatov and Sots Art painters. But nobody knew artists who continued to live in the USSR and later in Russia, but were deeply engrossed in their art practices. They did not join the politicising underground or dissident movement; their nonconformism was absolute and they remained true to their own artistic pursuits. Such dedication to art defined the highest quality of their artworks. Artists like Marlen Spindler, Igor Vulokh, Alexei Kamensky, Yuri Zlotnikov were concentrated on what they were doing in art and they did not use the political situation to promote themselves– did not participate in rallies or threw their passports away, when they landed in the West, or else. It would have been highly unlikely that Marlen Spindler participated in the legendary Buldozer Exhibition (note: took place in Moscow in 1974) – he cared so much about his artworks – each one of them – that he would never have brought them to an action like that. Works of such artists who were devoted to what they were doing form the core of our collection.

Alexei Kamensky, A Flame in a Fireplace №6, 1996

How do you combine commercial and non-commercial activity in gallery operations? At what stage have you started publishing your impressive projects in several languages?

Within the framework of our activity – you may call it popularizing or educational work – we started publishing catalogues, monographic editions and art books. It's hugely important to us. I know this feeling so well: when you discover something, you cannot keep it only to yourself but want to share it and these books in three or four languages are exactly the way which allows to do that. We have published over 30 catalogues, books and monographic editions. Furthermore, we produced some documentary films on various artists that had been released for the exhibitions: it’s sometimes difficult for a Western viewer and collector to understand an artist and his legacy, and thus he had a better chance to delve into the creative world and personality of this or that artist. And to grasp the essence in some 10-minute-long films.

In what way has the foundation become necessary to continue your activity as a gallerist and art collector?

A crucial factor that has prompted us to launch the foundation was the desire to realize various projects in museums which are always more willing to work with foundations rather than commercial galleries. We have several museum projects to our name (Marlen Spindler’s retrospective at the Tretyakov Gallery in 1996, the group exhibition “Unofficial Meeting” at the Russian Museum in 2012, and “Marlen Spindler. The Vologda Period” in Vologda in 2015. However, to develop this trend even more actively, we had to wait till the formal registration procedure was completed. The registration had taken nearly a year and, after finally getting the requisite papers in late December, we decided to mark the 25th anniversary of the collection and the opening of the foundation with a group exhibition of our gallery artists. We have planned soirees and musical events within the framework of this exhibition. Of course, it’ll take us some time to refine the new forms of operation, however, we’ll stage another exhibition jointly with the Shchusev Museum of Architecture already in late August, presenting works of the Swiss artist Richard Lohse alongside those of the Russian sculptor and artist Vladimir Andreenkov. The idea is to juxtapose Andreenkov’s works of the 1970s with Lohse’s legacy of the same period. The Pro Helvetia Swiss Arts Council (https://prohelvetia.ru), which has of late stepped up its activities in Russia, will also take part in this project. The Museum is currently negotiating the project with the Council to determine the scale of its involvement.

Igor Vulokh. Evening. 1970

How important is your Moscow venue in the overall gallery strategy?

Both venues are equally important but their tasks are different. The one in Zurich was set up to show Russian art to the Swiss and other Europeans, but showing Russian artists to the Russian audience is an altogether different matter. Many artists of that time turned out to be unknown for the Russian audience, especially for a younger one. At some stage we faced a paradox: Marlen Spindler was known to many in Switzerland and here in Russia few people heard his name. It's extremely important when we see Russian artists returning to the homeland. But this miracle happened when we opened the gallery in Moscow in 2010. We realized how much their art was in demand here.

Public at the opening of the Nadja Brykina Foundation

What is the role of cultural diplomacy in our politically charged times? Now and then we hear about a decline of interest in Russia and maybe Russian art as a consequence. Is it fair to generalize?

To a degree, the general situation which is not very favourable now, has had some impact on culture – if we started now and not 15 years ago, it would be more difficult. On the other hand, this time was not wasted: people and professionals trust me in what I do as a gallerist and whom I present. I would also like to add that the economic situation also changed and not only in Russia – Europe has been affected as well. Despite the fact that Switzerland is considered a neutral country with balanced views, people who are not well–informed, have some prejudices about Russia. They are more affected by the general atmosphere. At the same time, we cannot help mentioning the extensive work done by the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia which has a lot of interesting projects in Russia. Our gallery in central Moscow is located very close to the Swiss Embassy, and I sincerely hope that we will be developing closer cooperation – speaking figuratively and directly. I would like to add that several years ago, when the political situation was less tense, we presented the Russian sculptor Vladimir Soskiev at the Bad Ragaz Triennial Festival of Sculpture. Or in Vaduz, the capital of Liechtenstein, where sculpture is brought from all countries and continents for the festival, but in the past years Russia was not represented there. If we look at Art Basel, there is a huge number of American galleries there, and one can come under the impression that all art is concentrated in America. There are no Russian galleries due to both the political situation and protectionism in cultural policy. We are not that active at art fairs at the moment: I’m more focused on our gallery personalities and don’t pay that much attention to Swiss artists, who may be just as interested in being present on the Russian art scene. We would like to develop along these lines by offering partnership venues in Moscow, to say nothing of our own gallery. The forthcoming exhibition at the Museum of Architecture will be such joint venture.

Works by Y. Zlotnikov , Olga and Oleg Tatarintsev and B.Otarov in the space of Nadja Brykina Gallery

Do you work with any Russian artists of a younger generation?

As a gallerist I would be very keen to discover something really talented and truly amazing in contemporary art, and I’m more than sure it exists. But at the same time it’s no less important for me to keep up the traditions of our gallery. Speaking about a younger generation, we have some gallery artists who are disciples of the Nonconformists – they have kept their philosophy, but found a modern art language to convey their ideas. I could name Mikhail Krunov, whose mentor and teacher was Alexei Kamensky; it’s impossible not to mention the distinguished Russian artists Olga and Oleg Tatarintsev, husband and wife and an art duo, who through the use of their laconic and succinct plastic language respond to everything happening in society and the world today.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:02 30.01.2019 •

12:02 30.01.2019 •