Konstantin Yuon. ‘August Evening’(1922)

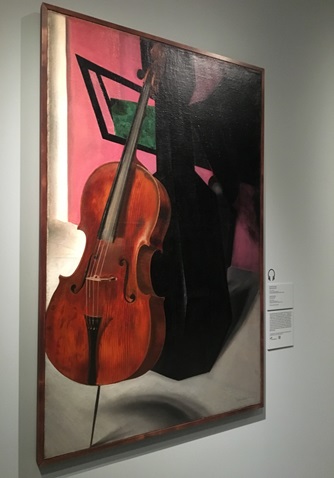

The Museum of Russian Impressionism presents ‘Other Shores. Russian Art in New York. 1924’, a research exhibition about the largest US show of Russian paintings, sculptures and graphics by a hundred prominent artists. The exhibition, now almost a century old, took place in the spring of 1924, and, until recently, was a significant, yet underreported chapter in the history of Russian art of the 20th century. Russian and American art historians have been preparing the exhibition for almost two years, and today the Museum of Russian Impressionism showcases more than 70 iconic works from the museums and private collections in Russia and around the world. The show includes paintings by Leon Bakst, Igor Grabar, Boris Grigoriev, Mikhail Larionov, Ilya Mashkov, Pyotr Konchalovsky, Boris Kustodiev, Zinaida Serebryakova and other artists. Two masterpieces ‘Officer’s Barber’ by Mikhail Larionov and ‘The Cello’ by Vasily Shukhaev were brought to Moscow from the collection of the Albertina Gallery in Vienna.

Mikhail Larionov. ‘Officer’s Barber’ (1907-1909)

Courtesy of the Albertina Gallery

During the project, some works were rediscovered. That was the case with Konstantin Somov's "Old Ballet" dated 1923. Kept in a private collection for more than 90 years, it was inaccessible to the public until the researchers found the piece on sale at one of the American auctions.

The current research exhibition is not a remake or reconstruction, but rather a dedication to the exhibition which took place in the USA almost a hundred years ago. Besides the search for paintings, the museum's art historians have set themselves a broader task - to study the multi-layered artistic developments which took place in Soviet Russia in the early 1920s. It is precisely archival research that has been a crucial part of the work behind the current exhibition. This wide-ranging detective work evolved at a time of the pandemic and unprecedented restrictions. However, the support of colleagues worldwide made it possible to progress. As Olga Yurkina, the exhibition curator, mentioned at the opening, "the project has once again convinced me that the museum community, connoisseurs, staff members of auction houses, libraries, collectors, and art dealers have shown themselves to be at their best. We are extremely grateful to everyone who helped us produce the exhibition".

Konstantin Somov. ‘Old Ballet’ (1923) Private Collection.

Speaking at the exhibition opening, prominent American art historian University of Southern California Professor John E. Boult explained that "there was no single archive, but a lot of scattered materials in various sources, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in the so-called, Bakhmeteff Archive - there are letters, photographs and even bills related to the New York project. Unfortunately, due to the restrictions, I was not able to conduct research in the archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There are still a lot of mysteries, and I have no doubt we will come back to this".

The scale of the 1924 project is impressive even by modern standards. Approximately 1,000 works by a hundred Russian artists were on the display in the Grand Central Palace, in the heart of Manhattan. The artworks literally sailed to "other shores" on transoceanic ships, and not only from the USSR but also from other countries - France, Sweden, where many emigre artists had settled by that time. After the end of the NY show, the Southern and Northern Traveling Exhibitions were formed, and the works of Russian artists toured across America and Canada for almost two more years. Subsequently, many works were sold and dispersed around the world.

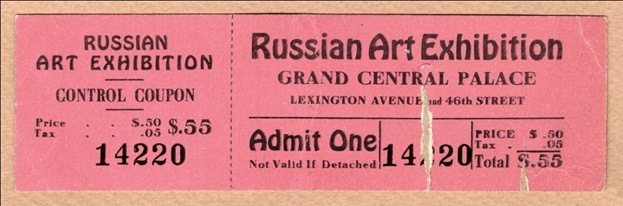

Ticket to the NY exhibition. (1924) Russian Culture Fund

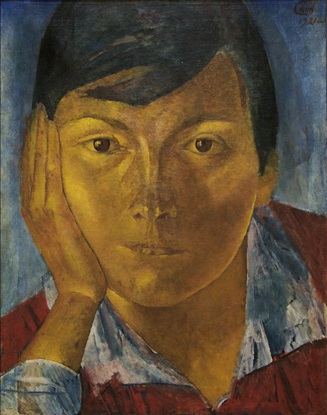

American papers of the time wrote extensively about the travelling exhibition. Olga Yurkina emphasized that "the archives of newspapers and magazines helped a lot in finding works and their attribution". The catalogue, compiled and edited by Igor Grabar, was hardly a monographic publication we would imagine today: descriptions of the works allowed simplifications for the American public and translation inaccuracies. That's why the American press's references to the works were key to unravelling some of the assumptions. This was the case, for example, with ”Yellow Face” by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin and “Evening on the Black Sea” by Grigory Bobrovsky.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. ‘Yellow Face’ (1921)

The Chuvash State Art Museum

Speaking at the opening, the MRI Director Yulia Petrova emphasized that “Other Shores” was only the first stage of a major follow-up work. "We have been able to show about a third of what has been achieved during our research project. We have managed to identify more than 300 works from the 1924 exhibition. Some of them we were not able to bring back for political reasons, particularly those in museum collections in the USA. It proved impossible to bring from Japan a large-scale painting by Boris Kustodiev, a gift from the Soviet government

to the collection of the Japanese Emperor when he was enthroned. Also, some private collectors were not prepared to lend works from abroad to Russia."

Vasily Shukhaev. ‘The Cello’ (1921)

Courtesy of the Albertina Gallery

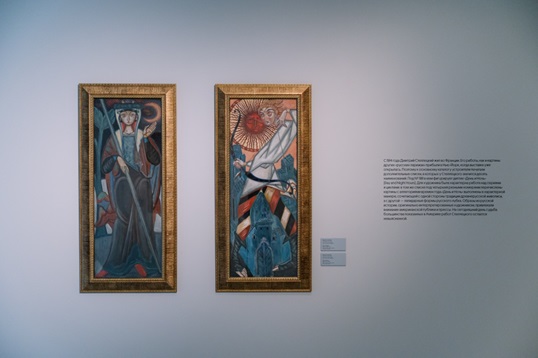

The third floor of the museum houses works by the Vasnetsov brothers, Stanislav Zhukovskiy, Dmitry Stelletsky and other artists whose participation in the American exhibition has not been documented. This part of the exhibition is called "Hypotheses". "We are showing paintings that might have been in America, but we don't have clear evidence yet. Nevertheless, we provide some arguments, and this allows our visitors and guests to try to penetrate into the laboratory of an art historian and try to assess whether you or some other painting could have made such an overseas journey," Olga Yurkina, curator of the exhibition explained.

"Hypotheses" Section.

Dmitry Stelletsky. Dyptich ‘Day and Night’

For a long time, perhaps the only available source for studying the events of 1924 were Igor Grabar’s and Konstantin Somov’s letters, two seminal figures in Russian and Soviet art, who represented the organizing committee of that exhibition. New opportunities opened up in the mid-2000s: "Rodina" émigré society donated a collection of paintings and documents related to that exhibition to the Russian Culture Fund. In the course of the current project, Russian art historians managed to join the efforts with their American colleagues.

In 1924, for the first time the exhibition organizers used the idea of a "national school" as a strategy to integrate Russian art into the American art market. From very early on, the exhibition was conceived as a commercial one, and the participants sent their best works across the ocean. Genres included the architectural projects by Shchusev and Fomin, sculptures by Konenkov, Golubkina and Kustodiev, works of applied art by such renowned artists as Somov and Chekhonin, numerous examples of Russian art and crafts. The American public also remembered the colorful poster created by Fyodor Zakharov based on Kustodiev's painting "Izvozchik" (Coachman).

1924 New York Russian Art Exhibition Poster

The American audience was introduced to Russian religious art and to many of the artists associated with Diaghilev's Russian Ballet. Although the exhibition was a unique cross-section of Russian art from the first quarter of the 20th century, as Professor Boult said, "it was a bit strange from the American perspective. The actual events of the time for Soviet Russia - the revolution, Lenin's death, the Bolsheviks - were not reflected at all in the works on view." Even the authors who supported the socialist system were included, but with historical, retrospective, nostalgic or politically neutral works. "If we talk about the general reaction of the American press to that exhibition, despite the fact that the USSR was then enemy number one, it was generally very positive. One of the prominent American art critics of the time, paying tribute to Russian art, even compared the exhibition to the Paris salon," Professor Boult noted.

Sergei Chekhonin. ‘The Grief’ (1921)

Surprisingly enough, apart from works by Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, who had long been living in Paris, no representatives of the Soviet avant-garde or even abstract art took part in the exhibition, although many artists of this genre had been widely exhibited in Europe. The avant-garde was not popular, albeit fashionable in America, but it wouldn't be long before this trend would make Russian art of the 20th century famous, becoming the most expensive and desirable commodity.

In the opinion of the researchers, two factors played a major role in selection of works for 1924 exhibition - the personal preferences of the project organisers, and a focus on the rather conservative tastes of the American public. The commercial aspect was put at the forefront in order to support artists in the USSR, many of whom lived in poverty at the time. "It is important to understand, that today we look at these paintings with entirely different eyes - as a treasure and Russian national heritage, whereas a hundred years ago, this was an exhibition undertaken with the aim of making as much money as possible", John E. Boult said at the opening ceremony.

Igor Grabar, Konstantin Somov and other members of the exhibition Committee

More than 90 works worth more than $50,000 were sold during the New York exhibition. Among the buyers were the designer Louis Tiffany, the businessman Charles Crane, Fyodor Chaliapin and Sergei Rachmaninoff.

The research will result in not just a catalogue, but a comprehensive edition with information on more than 200 works shown in the US. The exhibition is open until January 16, 2022, and is accompanied by an extensive educational programme for children and adults.

Images: Courtesy of the Museum of Russian Impressionism press- department

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:15 22.09.2021 •

12:15 22.09.2021 •