On January 29, 1942, an estimated 2,000 Italians resident in Kerch were ordered out of their homes and sent out to Kazakhstan in what essentially was an ethnic deportation authorized by Josef Stalin in retribution for the Italian military joining the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

Kerch was occupied by Nazi Germany on November 16, 1941 and liberated by the Red Army on December 30. Less than a month later, ethnic Italians living in Kerch started being deported for being “dangerous” and “collaborators.”

By the time of the second German occupation of Kerch (May 19, 1942 - April 11, 1944), the deportation of the Italians had already been complete.

The deportation lasted almost two months, from January 29 to late-March. During the long trip in jam-packed railway cars across Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, most of the children and old people died of hunger, cold and illness...

The deportees were taken out by sea from Kerch to Novorossiysk, on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, then in railway cars from Baku across the Caspian Sea to Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) and, finally, to Atbasar in Kazakhstan, where they were placed in shacks and temporary camps in Karaganda and Akmolinsk (now Astana).

According to official data, during the first year of deportation alone, one out of every five Italian deportees died. However, it would be logical to assume that the actual death toll was higher as it was wintertime and many simply froze to death. Rough estimates indicate that over 500 Italian deportees from Kerch died during and after the deportation.

It wasn’t until November 14, 1989 that the USSR Supreme Soviet finally declared the deportation illegal.

(Historical data was sourced from “L’olocausto sconosciuto: lo sterminio degli Italiani di Crimea” (Unknown Holocaust: Extermination of Crimean Italians) Giulia Giacchetti Boiko and Giulio Vignoli, 2nd edition, Rome, March 2008).

After the war, about 200 survivors began returning to Kerch where they had to start rebuilding their lives literally from the ground up, without houses, without work, without money...

A human tragedy, which has only recently come to light. A history of pain, but also one of great dignity, a never-ending love for Italy, the language and traditions of their ancestors.

There are more than 300 Italians currently living in Crimea, most of them residing in Kerch, where the Association C.E.R.K.I.O. (Comunità degli Emigrati in Regione di Krimea - Italiani di Origine) was founded in July 2008, led by historian Giulia Julia Giacchetti Boiko.

Unfortunately, after Crimea reunited with Russia, the Italians were not mentioned in the April 21, 2014 decree on the “rehabilitation of the deported peoples.” Still, during his 2015 meeting with Silvio Berlusconi in Yalta, President Vladimir Putin amended the decree by exonerating and recognizing Crimea’s Italian community as a deported minority.

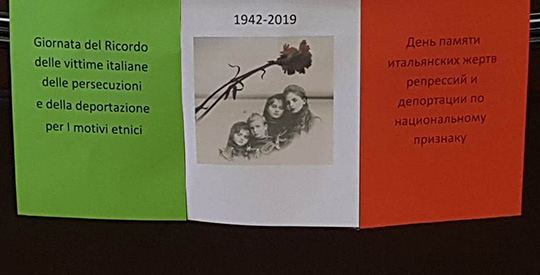

A "Day of remembrance of the Italian victims of repression and deportation," was held in Kerch on January 27 in commemoration of the tragedy, which has been annually marked by the local Italian community since 2009.

Italian MP Vito Comencini of the League Party took part in the Remembrance Day events, less than six months after visiting the local Italian community in August 2018.

Vito Comencini was accorded a warm welcome at the official ceremony by Kerch mayor Nikolai Gusakov, Giulia Giacchetti Boiko, and many members of the local Italian community.

Vito Comencini shared his impressions:

V. C.: “I was officially invited to the ceremony by Giulia Giacchetti Boiko, with whom I had already talked with during my previous visit to Kerch last year. As a politician, I have also come to convey institutional greetings. My visit is not only meant to commemorate the tragedy of the deportation, but also to show my affinity with my fellow Italians who live in Crimea today, to try to help them as a lawmaker and Secretary of the Foreign Affairs Committee, and generally to try to improve relations between Italy and the Crimea."

E. B.: During your previous visit to Kerch, you talked about giving Crimean Italians Italian visas and even giving them a chance to obtain Italian passports. What are the chances of making this happen?

V. C.: “Yes! I’m working to help young people, students of Italian descent, come to Italy for study or internship. They are Italian by origin, it’s true! During my visit, I also had the opportunity to see the situation in light of the sanctions. I’m saying it again: these sanctions are both unfair and wrong: they are impacting ordinary people and have no effect at all. It is all the more important, therefore, to preserve this connection with the Italians in Crimea. It is like opening another bridge, in addition to the Kerch one, to try to lift these sanctions as soon as possible.”

E. B.: What was the most emotionally-charged moment of the ceremony?

V.C.: “It was when, after the official meetings, we went to the seashore to lay floral tributes in the water in memory of the Italian victims who were deported on board a ship and died. We were silent for a moment, praying in our hearts, with the silence only broken by the splashing of waves.”

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

13:15 08.02.2019 •

13:15 08.02.2019 •